Hollywood loves a rags-to-riches story.

Little do we know – they may not be fully aware of it either – that their biggest success fits into this conventional narrative mold.

The Walt Disney Company, which was founded on October 16, 1923 and is now celebrating its centenarian glory, was for a long time an underdog in the business. A cute one maybe, but never a juggernaut and a media conglomerate that would go on to rank number 53 on the 2022 Fortune 500 US companies by revenue.

You may find it hard to believe, but Disney was nowhere to be found on the list of “Big Eight”, the eight major studios that formed the pillars of Hollywood. During Hollywood’s Golden Age, what was then known as Walt Disney Productions was an independent company and it did not move onto the “Majors” ladder until the 1980s. Now, of course, it can claim its royal lineage to that pantheon through 20th Century Fox, which was a bona fide member of the original “Big Eight” league and which Disney acquired in 2019.

If you study the early history of Disney, you’ll conclude that it has always clearly defined its parameters. From the very beginning, it has been keen on making family-friendly entertainment, especially animation. However, sharply delineated market positioning runs counter to expansion. Everyone knew what Disney exceled in, but few, if anyone, could envision its future beyond the horizon.

A happy ending for every episode

Every successful company has its ups and downs. Usually more ups than downs to even out the bumps and survive and thrive to this day.

The Disney story has its share of hits and flops, but they seem to spread out like a series, or long-format narrative in today’s parlance. The lights on the peaks are so bright that they help tide over the low points. For example, if they dramatize Disney’s history in the future, the first installment should probably end in the release of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”.

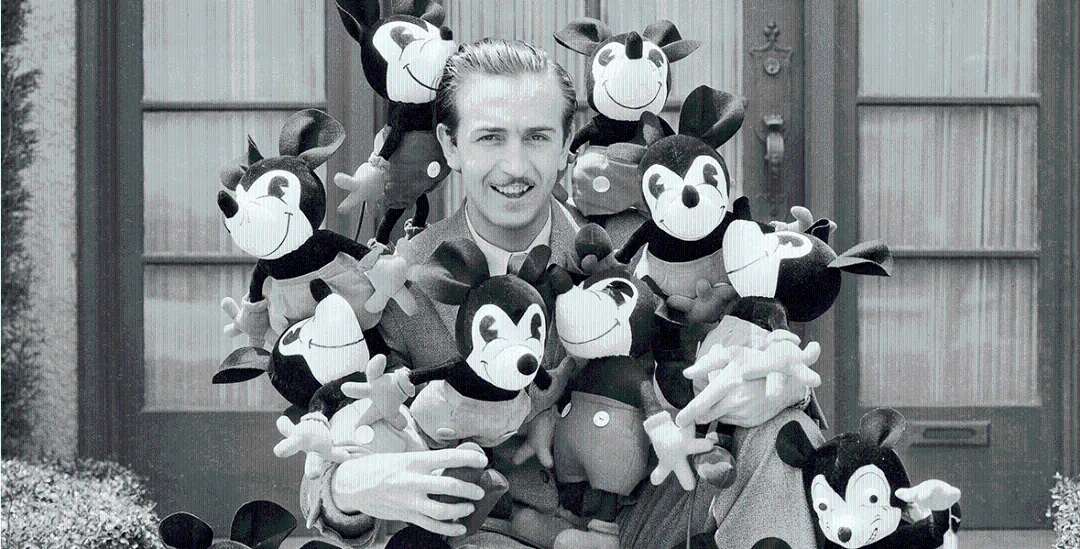

It would be insightful to watch Disney from his humble roots. I mean the person, the founder of the namesake company. One has to know this person to fully understand the company’s century of triumphs. Likewise, one has to more or less subscribe to his philosophy to dedicate one’s career to the running of this company.

Sure, Walt Disney (1901-1966) was not a perfect man. But the more I read about him, the more respect I have for him. He adopted a strategy of common sense. He took bold risks, but he was not the type of so-called “visionary” who would bet the house on white elephants.

When he decided to make the first animation feature in history, his co-founding brother objected and his Hollywood peers laughed it off as “Disney’s Folly”. But unlike someone who has never run a marathon but wants to unseat the current world champion, Walt had accumulated 11 years making animation shorts by that time. He knew the craft and how to innovate it; he knew the market and how to expand it.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was revolutionary to the outside world, but for those working on the inside, it must have felt like a long time of gestation full of uncertainties. For one, how would the reading public think of turning the original dark and brooding story into a happy and light-hearted one?

Disney’s second installment, so to speak, ended even more dramatically.

Walt did not spend a decade building mini-parks. Instead, he was traveling around the world, seeing the best of the existing amusement parks and, not remotely unrelated to his business or hobbies of a person of his age and stature, got hooked on riding small trains. His peers might have thought that he was ready for retirement.

Those disparate sparks coalesced into a place called Disneyland, opened in 1955. I remember the first time I set foot in this California park in 1986. It magically transported me back to my childhood. Funny that my childhood had nothing to do with anything in the park because China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) had completely deprived me of any knowledge of those children’s classics. So, it was an imaginary childhood, a childhood I did not have except in my belated dreams.

When I’m consulted by filmmakers who want to turn their screen stories into theme park attractions, I would ask: How long would the impact last for your film? A hit movie creates a buzz that extends a few months, and a hit series may go on for a decade. If you want your attraction to cover one generation, then you’ll have to appeal to at least two generations at the same time. In other words, it takes a franchise, not any franchise, but one with extremely long staying power, to give life to a roller-coaster.

Disney’s philosophy

I had the good fortune to tour the Disney facilities in South California in 1988 when I accompanied a group of Chinese television executives. It was then that I came into contact with the vast Disney realm beyond the animation classics and the theme parks. It was a souvenir store that made us stop and ponder: How to build a brand that could be embraced by people of all ages and all cultural backgrounds and whose merchandise seemed to attain a glitter of stardust?

Unbeknownst to me, I started my interest in the company right before the Disney Renaissance, when CEO Michael Eisner was steering it to a new golden age of animation by producing such critically acclaimed and commercially lucrative blockbusters as “Beauty and Beast” and “The Lion King”. Who cares they were not original tales? Shakespeare invariably relied on other sources, but it was his rewriting that made them great. Likewise, the Disney touch made its versions totally distinctive from the originals, in this case the French fairy tale and Hamlet.

Simply put, the Disney approach distills whatever sources of material into exaltations of the common virtues of humanity, i.e., love and compassion, kindness and decency. By eschewing a tunnel vision on one particular aspect of human existence, its stories, or the repackaged versions of the sources, have gained the capacity to resonate with the widest possible audiences. In this sense, Disney is the ultimate uncool because cool generally invokes the latest trends. But when most of the fads blow over and overstay their welcome, the Disney fantasies show very little wear and tear.

Of course, from the perspective of the trendy, Disney stories are passe from the very beginning, or old-fashioned, to use a kinder word. But that is exactly why its classics had little difficulty traveling from one culture to another. No matter what your language and custom, your religion or political belief, your ethnicity or skin color, let alone your age and gender, you’d feel comfortable watching one of those oldies. Yes, they’re tinged with the color of their times, but there is more timelessness than most “fashionable” adaptations that may endear one demographic while offending another.

Now, we have shifted from an age of common humanity to an emphasis on our differences. Either from an artistic or sociological point of view, this constitutes a rich minefield of narrative entertainment. But businesswise, telling a story with niche interest has very different commercial values than one that transcends all social boundaries. It is a worthwhile endeavor, but probably not worth investing US$200 million apiece.

I once asked Alan Horn, then president of Disney Pictures, about their movies’ focus on the bright side of humanity. He answered that Disney filmmakers were fully aware of the terrible things happening in our world, but they made their choice not ignoring the dark side, but rather, despite of it.

Horn said that they would come upon great scripts that did not fit their brand and regretted to see them slip through their fingers. The remedy, it seems, is to build or incorporate other brands owned by Disney but not culturally associated with it. It would be ironic to put the Disney logo on a Quentin Tarantino movie, but Miramax, independently managed, thrived in the Mouse House. Similarly, “The Handmaid’s Tale”, arguably the best show from Hulu, would have elicited bewilderment if aired on Disney+.

Under Bob Iger’s leadership, Disney got really big by acquiring Pixar, Lucasfilm and Marvel Studios. Their offerings snug comfortably in Disney’s much enlarged edifice of family entertainment. However, 20th Century Fox, now rebranded as 20th Century Studios, with Searchlight Pictures as its independent label, comes with all kinds of genres and franchises. It can be complementary to the Disney framework by creating stories that explore the murky waters of human dynamics.

It is in human nature to root for the little guy; it is also in the subconsciousness of some to want to see the big fellow fall. Now that Disney has constantly taken more market share than its Hollywood rivals, its base of detractors will grow. But if it follows Walt’s principle of common sense, it may have more victories than setbacks. The vitality of its many brands will be reinforced when they show their dexterity in the face of industry turbulences and the pitfalls of artistic homogeneity.

The Disney brand was loved all over the world before the company became a Hollywood behemoth. Whatever twists and turns came its way, it has been managed with loving care. The same is true of those consumers who embrace it. More than purchasing power, they have made an emotional investment in everything with its logo on it.

Entering its second century would be like having a season two of a popular series. We all want it to continue on the path of greatness, with variations and updates but not sharp departures from its core, which is to awaken the good, the humble, the empathetic in all of us.

By Raymond Zhou

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.