We’ve always been overinfluenced by the many rules and doctrines for as long as we live. These teachings seem to make our lives easy to understand and also keep us far away from the truth of the world. But we do not live in a vacuum – despite being shielded by conventional values, we will eventually face the true colours of the world. When such a reality of this world presents itself in a confusing and uncertain manner, many people struggle to accept it and may even experience mental breakdowns.

A good movie may have its greatest value right here, because it punctures the facade of this world in the most concise way and presents the realities that cannot be covered by concepts. Only in the face of those realities that are difficult to define, internalise, and forgo can our psychological world be truly elevated.

Edward Yang said in Yi Yi, "…we live three times as long since man invented movies." But this extension can only come about after you have seen many good movies, because no matter how many Marvel films or popcorn movies you watch, all you will ever get is superficial and fleeting mental stimulation, whilst your entire spiritual world will remain underdeveloped and forever be in its infancy.

In this sense, I think the most worthwhile movies to watch in life are those that free us from the ‘correctness’, those that are not prepared to cater to you, those that may hurt your self-esteem, or even those that make you lose direction in life.

On ‘love’: Love Letter

Love is the most dangerous emotion in the world, for it can make people lose themselves. You will always have two contradictory emotions in the face of true love – one is the desire to conquer, and the other is the desire to surrender. But between the two desires, the latter is stronger and more realistic/common, while the former is more of an instinct to escape the feeling of wanting to surrender to the other party; it’s the want to alleviate the inherent weakness through conquest and control.

Therefore, when one falls in love, it’s easiest to breed a sense of inferiority. In other words, a love that does not make you feel inferior is not real love, it is more of a friendship with intercourse sprinkled in. Hence, the purest form of love is secret love, a love you keep to yourself.

Love Letter by Shunji Iwai is the best film about secret love. When dealt with the unbridgeable void between life and death, the female protagonist recalls the memories of the boy who shares the same name as her. The boy yearns for the girl's attention, but his pride makes him instinctively unwilling to give in, and his insecurity makes him afraid to confess. The existence of these two emotions meant he was only willing to use bullying as an indirect method to get her attention. When he wrote his name on the library card, he was also writing her name as well. This bittersweet truth is only revealed to the protagonist by accident after the boy dies in an accident years later.

The film beautifully captures the blending of gain and loss, tragedy and sweetness, creating a unique kind of imperfect beauty that is distinctively Eastern. Something so light yet so heavy, so obscure yet so frank.

On ‘aspirations’: Revolutionary Road

An aspiration is not just an ideal, it is also to a certain extent, an excuse used to convince oneself that one is not mediocre.

As human beings, it is natural for us to dream of higher pursuits after meeting our basic physiological needs such as eating, drinking, and shelter. Such higher pursuits demand greater effort, perseverance and wisdom, but sadly, most of us are mediocre. We are willing to bask in the glory of realising our dreams, but few of us are actually willing to push ourselves for that so-called aspiration.

This is when the aspiration becomes a mere fig leaf, creating an illusion that we, as individuals, are completely different from all other living beings. In this illusion, our wretchedness and dullness become expedients for us to live harmoniously with the world for the moment, while deep down in our hearts, we believe we are a unique existence, distinctive from everyone. We use such illusions to deceive ourselves, to deceive others, and then use their reactions to our lies to further strengthen our self-deceptions.

But when the time to make a real choice comes, we’ll realise that we’re simply hypocritical creatures. At this moment, all the imagined romance turns into risk and danger, and the mundane routine we despised suddenly seems like a comforting and stable refuge.

Revolutionary Road portrays this very accurately. For this middle-class couple, their dreams and aspirations seem beautiful only when they are abstract and unpursued. Once they start actively working towards their goals, they are forced to confront a harsh reality – they are vain, cowardly, and reluctant to face their mediocrity. They are merely enamoured with the illusion of idealism, preferring the comfort of constraints over the challenge of genuine freedom.

On ‘reality’: The Matrix and The Truman Show

Lacking a sense of existence is a modern affliction, an unbearable lightness in life that inevitably arises after the material life and world is relatively developed. It is also a ‘petty bourgeoisie disease’, or ‘aristocratic disease’. In less technologically advanced times, humans spent most of their energy to obtain the necessary materials for survival, and all their mental resources was exhausted just for that. They simply didn't have the energy to notice certain unfulfilled psychological needs.

One of the most obvious symptoms of lacking a sense of existence is doubting the world in which we exist.

The Matrix and The Truman Show both touch on this issue from two aspects. When we take the time to closely examine our surroundings, we may become anxious about whether our world is truly real.

This doubt about reality reflects a deeper, more challenging problem that’s hard to recognize: the extent to which society controls us. It’s just that both movies depict this notion of control in extreme and dramatic ways.

In The Matrix, individual human beings become a source of energy; in The Truman Show, individual human beings become a source of mass entertainment.

In both films, individuals are merely pawns in a larger system. And this is indeed a reality to a certain extent. The very essence of society is simply a small group of elites legally exploiting and enslaving the vast majority of people. You are assigned a fixed social role and assigned corresponding values to ensure that you can play the role of the exploited with peace of mind and a sense of worth.

This system is so elaborate and refined that it almost seems invisible. The control it exerts is so subtle and pervasive that you’d think it's part of the laws of nature.

These two movies reveal this secret using different perspectives, allowing everyone to find the source of their underlying uneasiness. It isn’t merely a conspiracy theory imagined by idle minds; it reflects a real and omnipresent world that we are often reluctant to confront.

Regarding ‘memories’: Life of Pi

Are memories real? Not necessarily.

Is altering memories necessary? Yes.

Ang Lee's Life of Pi depicts this point subtly but cruelly.

When reality is devastatingly tragic, human rationality simply cannot withstand it. Our memories will automatically transform into something more amiable so we can make peace with our past.

From this viewpoint, all memories are shaped by our current psychological needs, and history itself is simply the interpretation of reality that benefits contemporary people.

In other words, it is our philosophical interpretation that determines history, and not history that determines interpretation.

Self-deception is not only a morally questionable bad habit; it is also a necessity for survival. Only through self-deception can we have self-affirmation and maintain the pretence needed to face the future calmly.

Regarding ‘institution’: Threads

Institutions are creations of men, yet they develop lives of their own, complete with their own desires and objectives. It is a huge quagmire that erases everyone’s ambitions and sense of justice through day after day of mundanity, fatigue, and the ravages of time.

Threads can be said to be a rare realist masterpiece in the contemporary era. It uses Baltimore in the United States as a microcosm to analyse the interconnected and inefficient ecology of a large and complex system: the bureaucracy is complacent, politicians are do-nothings, various departments are all busy undermining each other, and all kinds of intrigues are played between superiors and subordinates. In short, the institution becomes a rigid and ineffective machine, bogged down in pointless work.

The drama starts with a story about a crackdown on drug operations. It slowly and clearly portrays the redemption and downfall of even the most minor individuals in society, as well as the dysfunction hidden within seemingly perfect institutions.

In this expansive social landscape, social problems inevitably worsen. The elites within the institution feign morality and dispense justice to advance their careers. Individuals with a conscience and those who genuinely care are gradually marginalised by institutions, and then they fall silently in the dark corners of society, disappearing into obscurity.

In this ecosystem, there are no truly malevolent individuals, nor is there the perfect justice often portrayed in movies. Everyone is just a struggling survivor within the system, trying to live with either strength or humility amidst the darkness. Each tragedy mirrors another, and everything is gradually falling apart like a slow, boiling frog. While no single person can be held accountable for this systemic tragedy, everyone carries some measure of guilt.

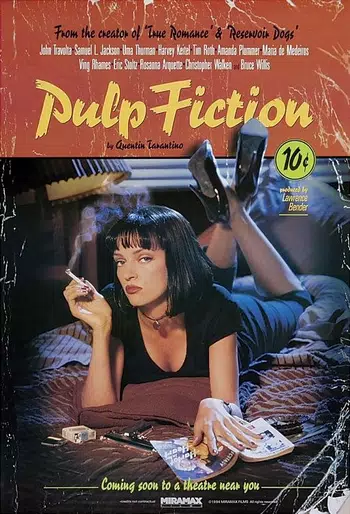

Regarding ‘cause and effect’: Pulp Fiction

Cause and effect is the basic principle through which we make sense of the world. Absurdity arises from the realisation that we cannot fully grasp or understand it.

Without cause and effect, our ability to describe and discuss the world diminishes. However, as we gain deeper insights into both the world and ourselves, randomness increasingly takes the place of cause and effect as the underlying essence. In other words, randomness becomes the core of what we previously saw as causal relationships, even though it contradicts the notion of cause and effect.

Pulp Fiction attempts to blend cause and effect with absurdity through artistic means. Under Quentin Tarantino's direction, the concepts of good and evil become the primary principles governing causal relationships, while absurdity subtly manifests between the lines. In the film, John Travolta plays a hitman who does not retire from his violent lifestyle after the opening scenes of murder and robbery, leading to his bizarre and senseless death on the toilet. In contrast, Samuel L. Jackson's character seems to have distanced himself from the criminal world and escapes unscathed.

Tarantino appears to embrace postmodernism, viewing this absurd world with a sense of irony. Yet, on a deeper level, he acts as a guardian of classical morality. Destiny, or absurdity, serves as a seemingly indifferent but precise moral judge. No matter how arrogant or clever a person is, he will get his due retribution for something unexpected and seemingly irrelevant.

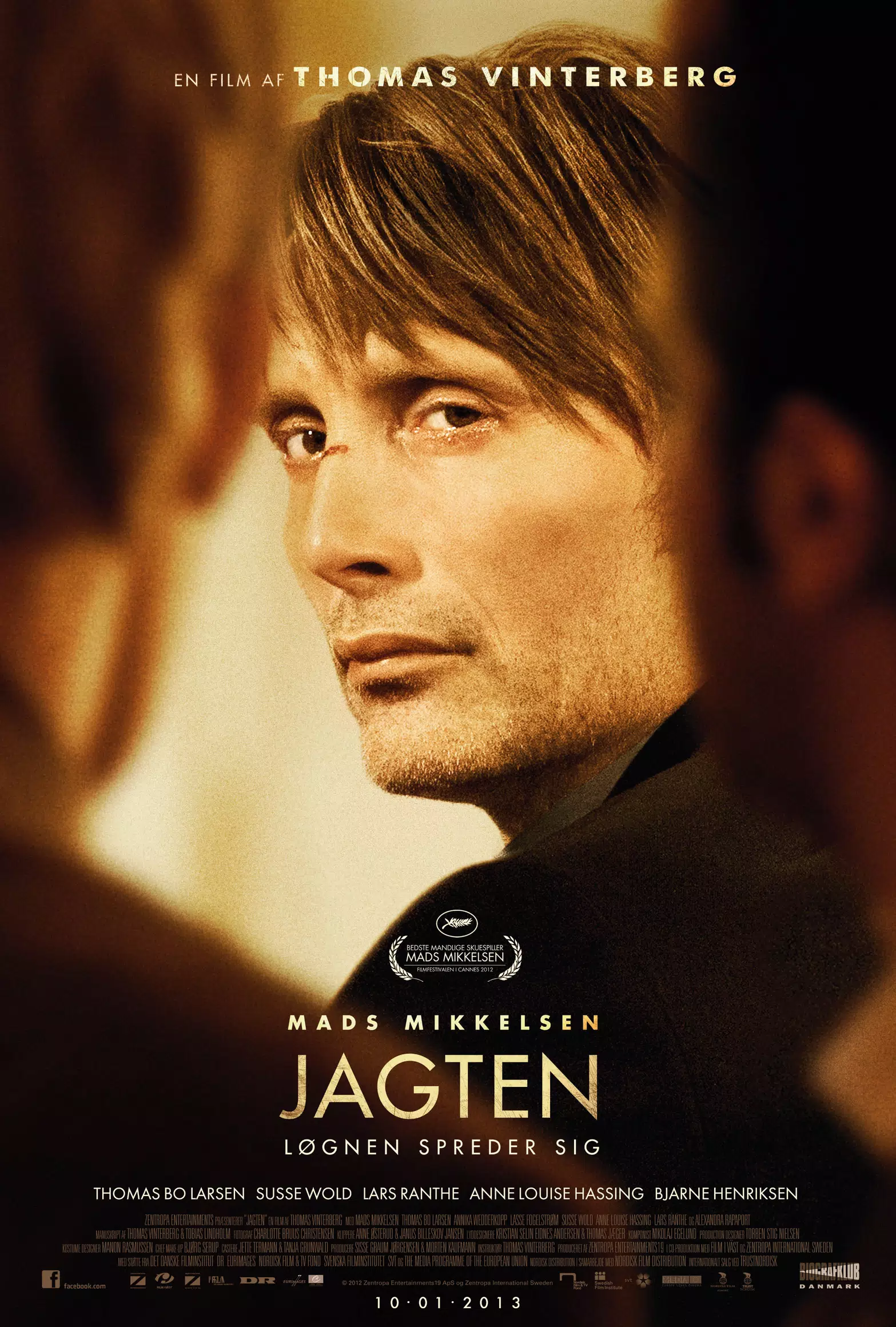

On ‘youths’: The Hunt

If ‘love’ is a concept that is mythologised by modern society, then the word ‘children’ is mythologised to an even greater degree.

In the conventional sense, ‘children’ are the opposite of ‘adults’, and ‘adults’, correspondingly, is a word with an obvious negative connotation. ‘Adults’ represent hypocrisy, snobbery and ugliness, while ‘children’ represent innocence, kindness and beauty.

The Hunt interprets the "innocence" of children from another aspect. This innocence stems from the animal nature in them. Children lack a clear understanding of good and evil, which means their behaviour can blur these boundaries. They are like beasts, expressing their needs or desires directly. When they don't get what they want, they will retaliate without hesitation. Because children have no idea of boundaries, the harm can be more severe than they realise, and because of what the word ‘child’ implies, the opposing adults are trapped between a rock and a hard place.

The evil of human nature does not only exist in adults, but also in children. The only difference is that adults will either restrain or indulge this kind of evil intentionally, while children express evil more naturally, for morality or empathy does not mean anything to them yet. Because they are creatures of baser instincts, their eyes are often alight with innocence.

On ‘acting’: Lust, Caution

Ang Lee's Lust, Caution is a powerful deconstruction of the so-called grand narrative, but what’s even more captivating is how it highlights the art of performance.

In reality, we are all inevitably putting on an act, but this kind of performance is not enjoyable because we are putting out another version of ourselves, and an image the real us need to be responsible for. In contrast, we are not ourselves in a real performance, and because of this detachment, we are better able to express our true emotions as we do not need to be responsible for it. In other words, only under a mask can true emotional expression be possible, though emotional expression itself is just a mask or a tool in reality.

The acts of pretence for the special agent Mr. Yee made the protagonist Wong Chia Chi realise that this facade is more genuine than reality, so she decides to remain in falsehood and never return to reality, choosing to let Mr. Yee go. She uses death, the most dramatic event, to quickly end her humble and dismal reality.

On ‘heroism’: Seven Samurai

A famous saying goes: “There is only one heroism in the world: to see the world as it truly is, and to still love it.”

This is the case in Seven Samurai. The peasants the Samurai wanted to save seemed cunning, selfish, ungrateful and afraid of death, but these samurai still died for them. They knew it was not worth dying for them, but they did it anyway.

Another saying is “I love you, but it has nothing to do with you.” In this film, it is “I’m dying for you, but it has nothing to do with you.” This is probably what true heroism is. It is not an exchange of favours nor guilt-tripping. It is a kind of softheartedness, a kind of empathy one cannot ignore, and it does not change because of the victim’s attitude.

In a way, the samurai also died for themselves, for their dignity, their pride, and their spirit of self-sacrifice. Death became the most relaxing and liberating moment in their lives.

All heroic actions are essentially self-fulfilment.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.