This year marks the 25th anniversary of Wong Kar-Wai’s romantic classic In the Mood for Love. To commemorate the occasion, Wong has re-released the film in selected territories, with a special addition: nine previously unseen minutes of footage.

What’s in these nine minutes? Could it be the much-rumored intimate scene between Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung that Wong once said he cut just before the film’s Cannes premiere? Or might it be a reworking of previously deleted scenes that had made their way onto DVDs? Hardcore fans of In the Mood for Love are likely familiar with these fragments: the awkward moment of physical closeness between Leung and Cheung’s characters in a hotel room, their late-’60s reunion at Angkor Wat, and Leung’s 1970s girlfriend growing suspicious and jealous of Cheung. These scenes are fascinating in themselves, but inserting them into the original film might disrupt its rhythm, tone, and balance—and potentially mar the audience’s memory of the original.

But debates about "ruining the memory" already surfaced when the 2020 restored version of the film was released. Since Wong Kar-Wai holds the rights to most of his films, he has full control to alter them—and he exercised that right. The 2020 restorations of Wong’s classics include many visuals and even dialogue changes. Fallen Angels had altered aspect ratios and color grading; Happy Together featured new narration; Chungking Express had remade opening and ending titles; and In the Mood for Love underwent a full re-color grade, shifting from its iconic red-and-blue palette to a yellow-green tone—visually transforming it into an entirely different film.

Reactions to this version were mixed. Many fans voiced their dissatisfaction with the new color scheme, criticizing it as a disrespectful “reinterpretation.” But Wong didn’t shy away from the controversy—in fact, he included a director’s note with the home release:

No one steps into the same river twice. Even if the river stays the same, the person stepping into it has changed. So I present you with my 2020 understanding of these old works.

The 2025 re-release uses this 2020 version as its main feature. So back to the core question: what exactly are these nine additional minutes that follow the main film?

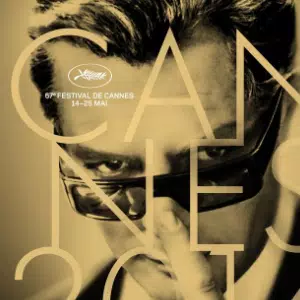

The answer: they aren’t closely tied to the original story. The footage is a contemporary short film starring Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung, shot around 1998 or 1999. Interestingly, it was shown once at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival under the title In the Mood for Love 2001.

So what’s its connection to In the Mood for Love?

To answer that, we need to go all the way back. Wong Kar-Wai’s Happy Together was his cinematic response to the 1997 Hong Kong handover. To distance himself from the looming political shift, Wong took his crew to the furthest place from Hong Kong—Argentina—to make the film.

With Happy Together complete and 1997 behind them, the handover remained a dominant concern. Having filmed the last movie as far away as possible, Wong now chose to do the opposite: his next project, Summer in Beijing, was set in the city most symbolically tied to the handover.

Wong cast Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung in leading roles and envisioned a lighthearted romance akin to Chungking Express. However, China's film authority rejected Wong’s scriptless working style, and the project was scrapped, leaving behind only a few promotional stills for investors.

With Beijing no longer viable, Wong returned to Hong Kong, still holding onto his idea of a light, romantic film. He began working on a new anthology about three food-themed love stories, again echoing the structure of Chungking Express. The first story, set in modern-day Central, Hong Kong, was filmed quickly. It starred Leung as a convenience store owner and Cheung as a frequent customer who loved beer and cake, entangled in a rocky relationship with her boyfriend. One day, the two heartbroken individuals find themselves alone in the store. After finishing her cake, Cheung’s character falls asleep at the table. Leung gently brushes cake crumbs from her lips with his own—marking the start of a new romance.

Sounds familiar? That’s because In the Mood for Love 2001 is the spiritual predecessor to My Blueberry Nights. After finishing the first segment, Wong moved on to the second—set in the 1960s and focused on lies and jealousy. Meant to be a quick shoot, it grew increasingly complex as Wong immersed himself in the period. He abandoned the three-part structure and expanded the second story into a full-length feature—what we now know as In the Mood for Love. The original short was left behind, screened once at Cannes, and shelved thereafter.

Now, in the 2025 re-release, that short reappears after the main film—a thoughtful gesture for longtime fans. We’re so familiar with the doomed, yearning love between Leung and Cheung that seeing them in a parallel timeline, with a different outcome, brings genuine delight.

The short also contrasts with the main film in its take on love. Set on the eve of the new millennium, it oozes postmodern consumerism: love, like convenience store snacks, is disposable—if one flavor doesn’t suit you today, try another tomorrow. By contrast, In the Mood for Love treats emotional commitment as a lifelong vow—something not to be entered into lightly or abandoned easily. That’s why its protagonists ultimately miss their chance, lost in hesitation and self-restraint.

Whether playful or serious, restrained or overt, Wong Kar-Wai masterfully captures romance’s atmosphere with his signature visual and auditory style. He uses step-printing to depict a kiss between Leung and Cheung, juxtaposed with close-ups of cake—equating appetite with desire. While In the Mood for Love 2001 may not offer anything narratively groundbreaking, it still stirs hearts with its sensual style—reminding us why Wong remains an irreplaceable voice in global cinema.

"The short also contrasts with the main film in its take on love. Set on the eve of the new millennium, it oozes postmodern consumerism: love, like convenience store snacks, is disposable—if one flavor doesn’t suit you today, try another tomorrow. By contrast, In the Mood for Love treats emotional commitment as a lifelong vow—something not to be entered into lightly or abandoned easily. That’s why its protagonists ultimately miss their chance, lost in hesitation and self-restraint."

^^ that's a real nice paragraph

View replies 1

View replies 0