To critique Nolan’s Oppenheimer, one must first discuss his prior works.

Christopher Nolan’s films share two major foundations in actuality. First, the presence of Greek Tragedy. Second, the impulsiveness as well as flaunting of technical skills of a filmmaker seemingly steeped in science and engineering background.

The Greek Tragedy manifests itself in Nolan’s films through grandeur and compassion. Nolan elevates his works to explore the philosophical ideals of humanity no matter the type of base material and angle of content. Thus, he can transform even a popcorn flick like The Dark Knight into a chilling dystopian fable.

He loves paradoxes and has a deep fondness for Nihilism. Unlike many other filmmakers, he did not let his endearments turn him cynical, to judge and scorn at the world through dark humor, to watch the spirit of void tear holes at it, scorning all that is meaningful to us, or to keep a distance against all with cold malignance. Filmmakers like the Coen brothers, Guy Ritchie and David Fincher presented their understanding of the world through elements such as hippie’s “peace and love”, rock or punk; they trivialized deep and heavy concepts. Nolan does the opposite. Compared to the aforementioned, he maintains his unique form of solemn dignity.

Facing the same concepts of paradox and nihilism, his primary aim is not unravel them and in turn presenting himself as the sole awakened wiseman amongst a crowd of ignorants; instead, presenting a sense of self-elitism, bitterness and pain are the perennial themes. He is more interested in portraying the crushing struggles of an individual faced with such truths of life, no matter how weak or superficial these struggles might be. His presence shares likeness to Albert Camus, one of the flagbearers of existentialism. Both sharp and solemn, both lacking in humor. Because humor requires one to distance oneself from the situation.

However, I do believe that some of Nolan works are brilliant. In them, characters usually present themselves like Sisyphus. In Memento for example, the protagonist would rather immerse himself in the erroneous memory of unserved revenge than to face the blank bewilderment of lost memories. Compared to the pain of living his life, it is more unbearable to be aimless. In The Prestige, the theme of magic is just surface decoration. What the film really presents is a bloodstained reality of life: miracles are nothing but merciless enduring, discarding one’s care for emotional and physical pain and suffering, as well as burying one’s sense of self into the deepest, darkest depths where no one else may discover. The final victor is none other than one who could hold this perverted form of acting to the very end. In Inception, it merges dreams and reality. Our very existence is nothing but an illusion, an illusion with a past that we can neither bear to look at in detail nor confirm. In such a hopeless environment, one either gets drunk in its illusory ambience or escape to a more insufferable undetermined “reality”.

The same concept applies to The Dark Knight. The dystopian world of Gotham City holds such intensity: would one prefer to be the Joker, treating the world like a big dumping ground, forcing everyone to show their true ugly nature, and dying amongst the fighting and killing of humans whose beastly natures are released? Or to attempt the impossible, to withstand all the sins of the world and keep intact the sole remaining symbol of hope to protect whichever little faith the imperfect humanity possesses, and not become soulless beasts in the process? Interstellar explores the same concept from another point of view: would you rather watch your own family die to save everyone, or return to your family at the potential risk of ending humanity? Is one soul’s value comparable to the entire human race?

These characters, caught between a rock and a hard place, have the most difficult choices to make: to choose the lesser evil. That deep, intense tragedy and the pyrrhic struggle to the end against Nihilism becomes an epic clash between light and darkness. Such pain and martyrish elements form the core basis of Nolan’s films.

In comparison to exploring the perseverance of human nature, Nolan’s greater ability is to use commonplace but extremely clear methods to make substantial abstract concepts of life; he has a frightening ability to elucidate a story. In Memento, humanity is discussed via a form of extreme reverse chronology. Humanity’s utmost tragedy is displayed for us at the ending reveal. Inception turned dreams into an overlapping form of parallel reality. That intrinsic feeling of “A lifetime of dreams, a moment of reality” is presented solidly. Interstellar, on another note, intricately links our usual feeling of mystery with higher dimensions.

If the unexplainable yet undeniable paradox is the mightiest driver in Nolan’s films, his intricate and positively flabbergasting model of storytelling forms the most charming part of it, drawing crowds from far and wide. This superhuman ability of his allows clashing values to present themselves in concrete ways, although, to some extent, such presentation is simplified via brutal manners (as a pre-requisite). However, when the depth and ambiguity of the former marries and balances the unembellished characteristics and clarity of the latter, they become sophisticated. They avoid making the film too deep, cold and, in turn, rigid. They give Nolan’s films a form of complicated clarity. At the same time, they are simple, yet complex. It’s these two parts of his work that allows him to break the boundaries between serious and commonplace films, allowing him to become a filmmaker who commands modern day box-office sales around the world.

To be put simply, Nolan’s previous films are outward facing. Be it the content or the way they are presented, his relentless passion is displayed through mathematical precision. Audiences can follow clear and firm directions in his films, joining the characters as they embark on their mental and physical adventures.

——————————————————————————————————————

The special thing about Oppenheimer, is that it has become one of his most introspective projects.

The film has a relatively greater sense of Greek Tragedy. In turn, this created a more intense portrayal of moral anxiety than Nolan’s other works. Oppenheimer’s anxiety over his own dark thoughts, anxiety over choosing between his girlfriend and wife, anxiety caused by his love towards his children, anxiety over protecting the Nation’s interests, as well as the moral struggle of good and evil over the creation of the atomic bomb.

Such anxiety levels are discreetly echoed amongst Nolan’s other films. Nonetheless, they are scattered in such a manner that they made the movie idiosyncratic against its Nolan counterparts. One is unable to clearly grasp the true theme behind Oppenheimer, while such central concepts are painted in bright red letters across his previous works. Thus, his prior films attach their value conflicts directly onto their protagonists and antagonists; be it Dark Night’s Batman against The Joker, Hugh Jackman against Christian Bale in The Prestige, or Matthew McConaughey against Michael Cain in Interstellar, their struggle signifies the core battle of values of the show. From these struggles you will come to feel the chasms between people or societies, darkness, and the final emergence of eternal nobility.

In this film, however, one does not come to observe a clear adversary for Dr. Oppenheimer. In fact, anxiety and tension exists between Oppenheimer and his lover, his colleagues, his government, even his fellows who share the same values as him.

In Nolan’s previous films, every single conflict point throughout a movie’s progress are steps of a stairwell digging deeper and deeper into the inner world of its characters. The core, innate essential question always surfaces at the final moment; and in that moment, humanity’s brilliance shines through the characters’ decisions in the face of their greatest tribulations. We can encapsulate that in his previous films, each conflict point acts as a link on the overarching chain of logic, miss one, and the entire chain will collapse. And then… Nolan’s universe will most definitely collapse.

In this film, while conflicts between its characters are not indispensable to the logic of its plot, the film itself is more akin to a work of art: it uses each facet of its multi-faceted characters to puzzle together a bigger picture.

If Nolan’s films before Oppenheimer were mathematical, enclosed, then we could regard this one as poetic and open-ended. In simple terms, it is a film focused on describing forms of state, and its dramatic elements are but an outer shell.

It is exactly due to such difference in essence that unlike previous films, viewers are unable to see clearly the substantial and operational effects of each scene in Oppenheimer. Each scene is self-sufficient. Dr. Oppenheimer’s state of emotions, his care for societal movements, the turbulence of the war era, his indecisiveness over the atomic bomb’s development and his self-insecurity all has their parallel meanings.

And all these relationships, these uneven yet connected emotions ultimately paints a picture of an era, an era that is gloomy yet excited, but at the same time despairing. That which is common, that pervades through all the film’s relationships is what Nolan truly wants to talk about this time. In other words, the plot has taken a backseat in Oppenheimer. An ineffable atmosphere has instead become the main character.

This change is colossal, as the plotline of a movie is the roughest fundamental way of explaining this world. To focus on the state of a person instead is to describe the world in a more humbled manner. It no longer views logic as most important, no longer attempts to force out an answer, but starts to respect the ambiguous relationships between things. Poetry is born out of such attempts. The world is in pieces, and the state of being exists, yet in a blur, among them.

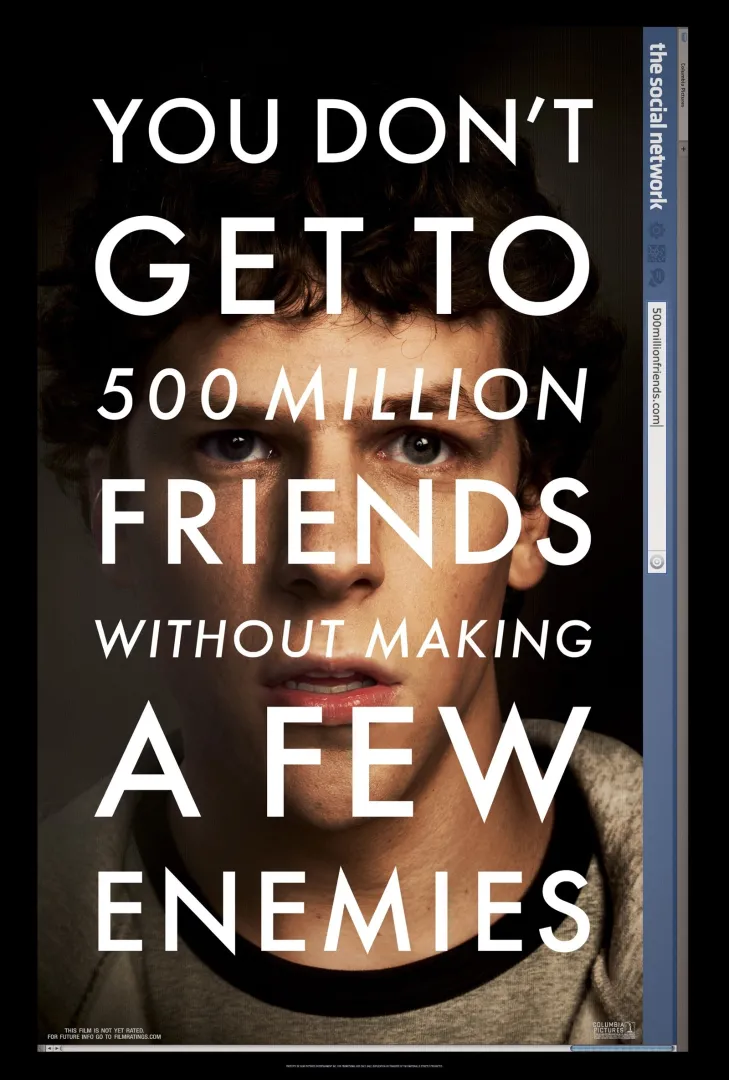

Thus in this film we do not see Nolan attempt in effort to find answers. To use David Fincher’s The Social Network as an example (as the two films are similar in this sense): both used a hearing as the angle of introduction to the story. But that’s it, that’s where the similarities end.

The Social Network seeks to clearly portray what kind of person Mark Zuckerberg is, and the key to that lies in the portrayal of the character, whose deeply ingrained grudge against the elitist club of Harvard: a commonfolk genius and his revenge against the upper echelons of society. It is new money born from a new age of internet. It is a gauntlet thrown against traditional capitalism and their old money. Zuckerberg gets the attention of the person he loves by pretending to be the jerk he is not. He builds the biggest business in the world to fill that initial lack in his heart. The Social Network in essence is the modern day Citizen Kane, and Facebook (now Meta) symbolizes Zuckerberg’s imperfectly hidden “Rosebud”.

However, Oppenheimer obviously does not explain why the protagonist becomes who he is to be. That is not the central point of the film. The film focused its energy on describing Oppenheimer’s abstract mental dilemma. This dilemma, in truth, is the collapse of civilization under the influence of modern day culture and ideologies. It is a person standing in the dark, displaying anxiety and fear after peeking into the future.

The era of the film is its true protagonist. Oppenheimer’s anxieties and meltdowns are but a reflection of the times. Such reflections span across physical bodies, careers, emotions and spirit.

So what kind of era is it? (Do I sound like a Taylor Swift fan? Hahahaha) One can only find out through discussion about quantum physics as well as the atomic bomb that manifested from it into reality.

Quantum physics’ greatest shock to human kind is its free flowing form. Its essence denies this world. It blows away all forms of certainty, as well as destroying all solid matter. It pushes nothingness onto center stage, making it the basic essence of the world. Without certainty, meaning disappears. This discovery did not come by simply due to a session of brainstorming by a philosopher, but proven as cold, hard truth by empirical experiments.

If we view the film from the above discussion, then as we discard the vague term “era”, quantum physics is then the true main character of the show.

This is the most impressive part of Oppenheimer, where it turned the “Main theme” of the story into an eerie but dazzling song about modern civilization, where the main score is written in Quantum physics and the atomic weapon derived from it.

Everything great and small thus surrounds this score in a resonating cacophony. The spirit and bodies of humanity twist and lament to it.

In this film, from the giant stars and blackholes in the universe to the minuscule atom and energy waves, all exude the same kind of aura: scintillating but desolate.

The swift (see what I did there ;) hahaha) progress of quantum mechanics coincided with the rise of modernism in literature and art. Therefore, as Oppenheimer is mired within the grandeur and coldness of quantum mechanics, he is at the same moment pacing between Eliot's "The Waste Land" and Stravin's Skir's "The Rite of Spring".

Among the various imageries in the film, the desert plain stood out in particular: Los Alamos, a desert plain devoid of anything, is the singular most important scene in the movie. It witnesses the birth of the atomic bomb, and in turn the opening act of destruction of the entire world. It is the only weapon that stopped World War II, but at what cost? A step forward world’s annihilation…

Death has become inseparable to this film. Its beauty and cruelty make the film’s characters both fearful and exhilarated. The film opened with an apple injected with potassium cyanide, an undeniably vivid imagery of death.

That impulsive unfounded desire for Oppenheimer to poison and murder his tutor, and his equally unexplained sudden reversal of the act is in fact a portrayal of his inner struggle between nihilism and reality. Instinctively, he cannot resist falling; instinctively, he cannot resist saving himself as well.

Due to such instincts, both relationships that the Father of the Atomic Bomb experienced turned into a process of uncontrollable mutual comfort. It is as if two people were forced to keep each other warm during a cold winter storm; it is done for the sake of survival, a basic manner of defense against impending death. Be it making love to Jean whilst reciting Sanskrit, or the passionately kissing Katherine in the middle of Los Alamos desert, none of them felt romantic. Instead, it feels like a drowning man trying to save himself, like two hopeless people treating each other like vines and climbing it for self-preservation. The winds of the universe cometh past and present simultaneously, and no one is resistant to its icy breaths.

Life has become an uneasy concept to exist in this film. Every time Oppenheimer’s children enter the scene, they are accompanied by anguished crying. In contrast, the most beautiful element in the film is represented by the flames during the detonation of the nuclear weapon; flames so merciless and yet gently dancing in the air, decisively devouring everything in its path.

Such intentional contrast further highlights the gloomy tones of the movie. The incessant droning of life and charming attraction of death create an environment of passionate apprehension, something never seen among Nolan’s prior films. This is also where Oppenheimer’s greatest value lies: this cold poetic feel brings about a kind of magnetic ambiguity, a first for his works.

The inner struggles of man in reality and the mysteriousness and emptiness of this world have become two sides of the same coin. They resonate enigmatically to the same tune. And it is precisely because of this that music takes a greater weightage in Oppenheimer compared to other films. These sounds and music are Professor Oppenheimer’s own inner voices. In the original soundtracks, the main melody is slightly inharmonious, flowing from low to high and so on. This is the reflection of Oppenheimer’s feelings: suppressive yet at the same time euphoric. It portrays the scientist on a volcano, yet at the same time in an ice cellar. In addition, the sounds of electric currents, stomping and various noise, like flowing lava, accurately paints Oppenheimer’s inner world. At the same time, these sounds portray the world in its actuality, and we are but dancers under their orchestration.

The intense pace of storytelling in the film is no longer designed for plot tension but has become a part of the entire atmosphere. It is the face of an era, one that is full of apprehension and moves swiftly and muscles everyone along with it. It is the footsteps of an era full of killing intent.

Thus the film’s grandeur is created through the simultaneous display of the desert, the atomic detonation, the panic in the entire society, as well as Oppenheimer’s own inner struggles. Those parts do not belong to the plot directly, they hold an equal importance to Oppenheimer’s actions.

And it is, in fact, against this gloomy, fateful, monstrous melodic backdrop does Oppenheimer’s chaotic, conflicting passion to save the world look vicissitudinous. Everything in the film is a symptom telling of its time: that desolation and magnificence, burning anxiety and emptiness, that disillusionment and hunger, that greed and fear, all soaked and condensed into every page of the film.

The greatest trait of this film lies in its poetic nature as well as its ability to understand the world through Oppenheimer’s mind. Thus, Nolan’s habit of over-dramatization hurt the film in certain areas. For example, Robert Downey Junior’s role as the main antagonist becomes the film’s greatest failure. This is because Oppenheimer’s real enemy are not the bureaucrats but the era itself, the era that brings both uneasiness and anticipation. The politicians led by Lewis Strauss can neither carry the weight of his mental energy nor carry values that can hold a candle against those of Oppenheimer’s. They are simply some jealous bureaucrats in the system who misunderstood the genius protagonist, much like Salieri’s unfounded yet firm resolve to make Mozart his mortal enemy in Amadeus (1984). This kind of iridescent and secular confrontation does not go in tandem with the inner abyss of Oppenheimer that the film really wants to talk about. Nolan dwarfed and narrowed the real contradictions in the film, and in doing so gave the audience a sense of mismatch and imbalance.

It is also undeniable that making the film poetic may cause some confusion amongst certain fans of Nolan’s, as the film has no actual plot climax. Be it the detonation or the heated arguments over the two hearings, they are at best accompaniment to the movie’s emotions, albeit the loudest ones. Thus the film differs from their predecessors: there is no concentrated release of dramatic tension derived from logic typical of Nolan’s works.

All in all, Oppenheimer is an admirable attempt of winning an Oscar. Before this, we were able to observe Nolan’s directorial exploration in another level: Dunkirk and Tenet. Regrettably, their storytelling seems to have gone awry. When Nolan struggles to find something that excites him in terms of expression, he tries to play more tricks with the form. Unfortunately, such methods are ineffective, as being overcomplicated will instead make a piece of work boring and unsophisticated.

In Oppenheimer, one can feel the imbalance in terms of plot, but like a volcano, holds explosive energy.

From this angle, how an expression is carried out is always more important than what the expression is. In this film, you can see Nolan’s efforts to break new grounds strain against his old filmmaking habits. Such a conflict brought out discomfort, but at the same time a rare momentous emotion felt due to his breakthrough. Such a feeling in turn carries a subtle and indescribable impact.

If there is something one cannot miss, it’s the grandeur. Where visuals are concerned, Oppenheimer is comparable to Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Andrei Tarkovsky’s, Stalker. Together, they attempt to elucidate the destiny of the entire human race, to scrutinize the essence of the entire civilization, and to measure our material and spiritual world on the largest scale possible. Oppenheimer’s inherent seriousness and sharpness gives the film a temperament rarely seen in Hollywood movies in recent years. Its solemnity and strong sense of morality brings forth an awe-inspiring experience to its audiences.

First published on WeChat | Official Account: Positive connect – ID: zmconnect

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.