When it comes to choosing the greatest Canadian filmmaker, who would it be?

We could consider a few candidates: for instance, James Cameron, one of the most commercially successful directors ever, regardless of nationality; or recent Hollywood darling Denis Villeneuve, whose unique aesthetic and personal touch have redefined big-budget blockbusters. After the success of his Dune series, Villeneuve will surely gain even greater influence in Hollywood.

However, both Cameron and Villeneuve are essentially Hollywood directors. Without the biographical details, it would be hard to tell from his works that Cameron is Canadian. Villeneuve’s cold, austere style does resonate more with a sense of “Canadianness,” but that local flavor is absent in his most influential works. And given his recent massive commercial success, it’s unlikely that he’ll return to making films in Canada anytime soon.

Thus, for this discussion, the most suitable choice is David Cronenberg, who happens to have his newest film The Shrouds shown at the recent edition of TIFF. This is not just a recognition of his Canadian identity—most of his films were funded by Canadian companies and shot in Canada—but also a testament to his artistic achievements. You could call him a master of the “body horror” subgenre, or a director who delves deeply into the relationship between the soul and the flesh. Yet, none of these labels fully encompass the breadth and depth of his work. As a matter of fact, both cinephiles and film scholars have coined the term "Cronenbergian" to describe his inimitable and indescribable style, making him a singular, irreplaceable figure in contemporary cinema.

So, why does Cronenberg hold such a prominent position in film history? What exactly does the term "Cronenbergian" refer to?

A Career Par Excellence

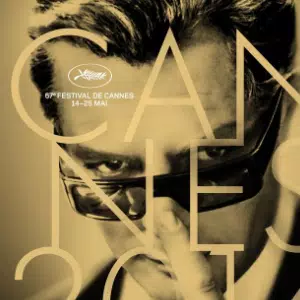

From a mainstream perspective, Cronenberg’s track record may not seem all that impressive. He has directed 23 feature films, none of which earned him an Oscar nomination. Though a regular contender at major film festivals, with recent works consistently making the official selection at Cannes, he has never won the top prize at any of these festivals, although the Berlin Film Festival did award him an honorary Golden Bear in 2018, for his lifetime achievement.

Yet, if we disregard the awards, Cronenberg’s career is massively enviable for most directors. He is a national treasure in Canada, having been awarded the Order of Canada, and Ontario has hailed him as “Canada’s most celebrated internationally acclaimed filmmaker.” Though he has never won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, he has served as the jury president and, in 1996, with his entry Crash, caused a heated debate among jury members led by Francis Ford Coppola.

He is both a master of B-movies and a darling of film scholars and serious critics, with the philosophical, scientific, and psychological layers of his films consistently exciting publications like Cahiers du Cinéma. Directors like Edgar Wright admire him, Guillermo del Toro reveres him, and Martin Scorsese finds his works deeply unsettling. As a filmmaker, you couldn’t ask for a more fulfilling career.

So, naturally, the question arises: what makes David Cronenberg such a cinematic legend? What is his place in film history?

An Assaulter on the Body and the Mind

Anyone who has thought deeply about the nature of cinema is aware of the medium’s authoritarian power: it can manipulate your responses through visual and auditory means, control your senses, lead you to accept its conclusions, while subtly instilling ideological messages into your subconscious. American writer David Foster Wallace once said, “Movies are an authoritarian medium. They vulnerabilize you and then dominate you.” Spanish film master Luis Buñuel had put it more bluntly: “Cinema is a vicious medium. Sometimes, watching a movie is a bit like being raped.”

If many commercial films, designed to stimulate the senses and provoke emotion, offer a metaphorical form of rape, then Cronenberg’s films often feel like literal assaults. His movies have a visceral, sensory impact because they genuinely threaten to invade your body. Consider these shocking images: a man’s stomach grows a vaginal-like opening where a terrorist inserts a videotape (Videodrome); another man’s DNA fuses with a fly’s, transforming him into a 6'3" human-fly hybrid (The Fly); a third man, after having a hole drilled above his hips, finds himself plugged into a spinal cord network, only to discover that the data cables carry a real virus (eXistenZ). In Crash, a woman develops a long scar on her thigh after a car accident, which she turns into a sexual organ and uses in a twisted encounter with a man who fetishizes such injuries.

Even in Cronenberg’s later works, which are less overtly grotesque, the presence of the body is inescapable. For example, the interior of the stretch limousine in Cosmopolis feels like a living, breathing, pulsating organism. The car exerts an overwhelming sensory impact, shaping our emotional response to the film, much like a monster rolling over you.

So, is Cronenberg simply a director obsessed with cheap sensory thrills? Absolutely not. His films don’t just invade your body; they also aim to assault your mind. In his works, physical mutations often lead to mental confusion: in Videodrome, after Max’s body is invaded, he loses all sense of reality and becomes a pawn for an extremist group. In eXistenZ, the two main characters become trapped in nested dreamlike worlds, unable to return to reality. And in Naked Lunch, based on the life of author William S. Burroughs, protagonist Bill Lee becomes a drug addict who cannot distinguish fantasy from reality, ultimately killing his wife in a delusional state.

In other words, as a director, Cronenberg is a rapist of both body and mind. Yet, for him, this distinction is meaningless because, as an atheist, he rejects the Christian and Cartesian dualism of body and soul. To him, the body and what we call the “soul” are one and the same. Therefore, to touch the “soul,” one must start with the body. And film is the perfect medium for this, as it cannot capture abstract concepts—it can only depict the human body.

When Cronenberg seeks to convey an abstract idea, he does so through visceral, fleshy imagery. Want to show the eroticism of writing? Alright, let us turn a typewriter into a talking insect that spews thick liquid and whispers dirty talk (Naked Lunch). Want to explore Marshall McLuhan’s idea that media extends the human body? Okay, let us open up our protagonist’s stomach and literally turns him into a human VCR (Videodrome).

Cronenberg’s philosophical views may explain why he is far more celebrated in Europe than in the U.S. In American society, the influence of puritanical culture remains strong, and many people still believe in the existence of the soul, a notion that Cronenberg dismisses with contempt: “People can’t accept the unity of body and mind because they don’t want to acknowledge that death is inevitable, and there’s no afterlife. The refusal to accept the reality of the body always stems from an inability to confront death. In contrast, I find it impossible to accept the existence of God or the devil because I can’t believe in an afterlife.”

Human Evolution, Cronenberg's Only Hope

Without hope for an afterlife, Cronenberg and his protagonists are anchored in the secular world. As a filmmaker working mostly with mid-to-low-budget films, his lens inevitably focuses on the mundane realities of everyday life. Yet, within these banalities, there are always key moments of secular revelation, prompting his protagonists to evolve and move into the next stage of their lives. This transformation and evolution often lead to tragic outcomes, but the journey itself is what matters most to Cronenberg’s characters, not the final destination.

In Cronenberg’s films, we’ve seen countless moments when a protagonist’s weary eyes light up with newfound fascination: when Max first watches the sadomasochistic show Videodrome; when Seth first realizes his teleportation project might actually work (The Fly); when undercover cop Nikolai is first provoked into violence by Russian mobsters in Eastern Promises. For Cronenberg’s protagonists, these moments are akin to a divine revelation—their previously monotonous lives suddenly take on meaning, and their sole mission becomes following this newfound “evolution.”

In Cronenberg’s world, “evolution” often refers to two specific changes: a shift in identity and a transformation in physical form. These two changes frequently conflict with each other: in The Fly, Seth’s physical transformation leaves him increasingly unrecognizable, even as his mental state becomes more energized and seemingly superhuman. In Naked Lunch, Bill’s creativity flourishes under the influence of drugs, but his physical and mental state deteriorates. In Eastern Promises, the tattooed code of the Russian mafia seeps into Nikolai’s being, making it hard to distinguish his true allegiance by the film’s end.

While Cronenberg doesn’t believe in the dualism of body and mind, the tension between the two continues to fascinate him. Why must the body disintegrate while the mind remains intact (The Fly)? Why does the mind collapse when the body is still functioning (Spider)?

Cronenberg witnessed such conflicts firsthand in his childhood. His father died of an undiagnosed illness that left his mind unaffected but rendered his body incapable of absorbing calcium, causing his ribs to break when he turned over in bed. His father died fully conscious, a haunting experience that shaped Cronenberg’s views on death and transformation. Perhaps only through romanticized narratives of disease can Cronenberg fully reconcile with the trauma of death. Thus, we see that in the early stages of transformation, his protagonists are filled with hope, even believing they are emerging from a cocoon as something greater.

Cronenberg's Place in Film History

The phrase “emerging from a cocoon” brings to mind one of Cronenberg’s literary heroes: Vladimir Nabokov. Cronenberg’s fascination with insects rivals Nabokov’s—he directed three films with insect-related titles: The Fly, M. Butterfly, and Spider.

In fact, Cronenberg originally aspired to be a writer. He wasn’t a die-hard film fanatic like Scorsese or Tarantino; most of his artistic influences came from literature. After making a name for himself with B-movies, he began adapting significant contemporary literary works: Burroughs' Naked Lunch, David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, J.G. Ballard’s Crash, and Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis. His stepping away from filmmaking in the late 2010s was driven by a desire to focus on writing novels, having once remarked: “Film is a very crude medium. Literature can convey many inner emotions and ideas that film simply cannot.”

Cronenberg’s creative approach is difficult to place within any established framework of cinema, as his thought process is deeply rooted in literature, absorbing influences from numerous literary figures. For example, when designing the appearance of the protagonist in Spider, he didn’t draw on past films about psychoanalysis but instead envisioned the look of writer Samuel Beckett, whose one-act play Krapp’s Last Tape came as an influence to this film. Even his use of camera lenses has literary associations: “A 75mm or 50mm lens isn’t a Beckettian lens, only a wide-angle lens is.”

So, where exactly does Cronenberg stand in the history of cinema? In terms of industry, he exists between the systems of Europe and America. His films often feature major Hollywood stars, and he occasionally secures American funding, but his long-term collaboration with a consistent team and his continued exploration of fixed themes resemble the methods of European auteurs like Éric Rohmer.

Aesthetically, it’s even harder to find a comparable figure. His blend of startling imagery with a cold, clinical tone may evoke Luis Buñuel, but Cronenberg’s social critique is more abstract, and his images are more directly aimed at the senses. His approach of turning internal mechanisms inside out, exposing both the mind and body’s mechanisms, is somewhat similar to Jean-Luc Godard’s method of revealing the internal mechanisms of cinema and society. However, their subject matter differs greatly. While Godard is intensely conscious of the film medium itself, Cronenberg merely uses cinema as a vehicle to express his intellectual musings.

Cronenberg is a unique figure in the history of cinema. He came from outside the world of film, yet through his unparalleled imagination, he added a whole new dimension to the medium. He rose from the B-movie ranks, a genre often dismissed by scholars, and, through his intellectual rigor, ultimately became a favorite of the art-house circuit. This cinematic journey is unprecedented and, in all likelihood, will not be replicated. There will only be one David Cronenberg.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.