The new British TV adaptation of The Day of the Jackal had garnered two Golden Globe nominations (Best Drama Series and Best Actor) even before its finale aired, and its current IMDb rating (8.2) briefly surpasses that of the 1973 original film (7.8). But for audiences familiar with the original film and novel, every aspect of this new series feels somewhat off.

Its failure is very much of our current era: it’s mediocre, lacking courage, eager to please, and tries to mask its inner emptiness with noisy music and flashy style—without success, as the gaping holes remain evident.

Eddie Redmayne’s portrayal of the titular killer, “the Jackal,” is charismatic. But that charisma comes from the actor himself, not the story. The script repeatedly embarrasses the character, reducing this iconic fictional assassin to a mercenary with no code and no ideals—verging on a mere terrorist.

So the aura that Redmayne painstakingly establishes through his nuanced preparation instantly deflates whenever “the Jackal” commits senseless killings or engages in petty, degrading acts—like pleading for help from his employer.

In the 1973 film, “The Jackal” killed only three people. In this new version, he’s on a wild spree, leaving a trail of bodies and clues, baffling viewers. This supposedly “one last job” assassin seems instead like someone bent on self-destruction as if he’s secretly yearning to be caught and put to death, just to stop harming the world. This “Jackal” is anything but cool. He’s more like Mr. Bean, constantly stumbling, tearing down one wall to patch another. Yet amid all this ineptitude, he somehow remains groomed like a male model, sporting impeccable outfits on the streets of Europe—never losing his star-like glamor.

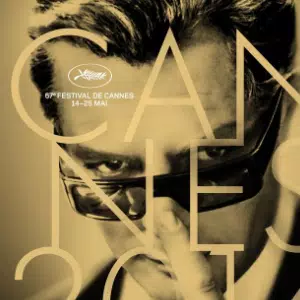

According to the creators, the Jackal’s ever-changing look is a nod to the 1970s rock'n'roll chameleon David Bowie. Such fashionable name-dropping wouldn’t be a huge problem if it weren’t for the general lack of genuine creativity these days. The real problem: this new Jackal’s motives and principles are all over the place. This confusion doesn’t stem from a rich, complex psyche; it’s simply poor writing.

From the Jackal’s backstory, we learn he once bombed fellow soldiers in Afghanistan because they massacred civilians without remorse, establishing him as a morally driven anti-hero. Yet right before this supposed righteous act, he’d taken a hit job during his vacation without the slightest curiosity whether his target was innocent or not. He also betrays his business partners and dear friends. If his final killing of a friend was out of self-preservation, then what’s the point of all the earlier empty threats when no imminent danger was present? Far from seeming cool, he comes off as timid and insecure. A truly dangerous dog doesn’t bark needlessly; one that does is often all bark, no bite.

The new Jackal, muddled as he is, still isn’t chaotic enough for the writers. They give him an entire family network: a wife, a child, a brother-in-law, a mother-in-law. Every assassin knows personal attachments are a liability—yet this “family-friendly” Jackal ignores that. The writers claim this adds depth, but it’s really just padding.

To understand how tiresome these extra plot lines are, let’s re-examine what the 1973 film did right. Director Fred Zinnemann, in his sixties and late in his career, showed more narrative agility than these younger creators. He wasted no words. His film is silent, aloof, like the assassin himself. That original Jackal had conviction and purpose; anything irrelevant he wouldn’t touch, anything blocking his path he would calmly remove.

The narrative efficiency of the 1973 version mirrors the Jackal’s own efficiency. In a crisp two hours and twenty minutes, the film is packed with information, every moment tense, leaving the viewer afraid to blink or breathe too loudly—lest this quiet killer catch you watching. The Jackal’s journey was a testament to his craft, and the 1973 film was a testament to classic Hollywood craftsmanship.

All these virtues have been discarded by the flashy yet meandering new series. What’s left? Just a contemporary update of the original and novel’s historical context.

In the original story, the Jackal’s target was French President Charles de Gaulle. Now it’s updated: first a populist politician, then a tech mogul controlling cryptocurrency. Correspondingly, the Jackal’s methods of evading borders, customs, and surveillance cameras are also modernized. Observing how the assassin’s techniques evolve with the times is one of the few pleasures of the new show.

But the tech magnate, pieced together from trendy buzzwords, is utterly unconvincing, rendering the Jackal’s final mission hollow. Killing one big shot won’t stop crypto from issuing coins. Issuing crypto can’t singlehandedly change the world. It’s unclear what the writers had in mind.

A belief in their material distinguishes the 1973 film from the 2024 remake. Regardless of the assassin’s political stance, you sense in 1973’s version that everyone involved—writers, director, cinematographer, actors—had faith in their story. The 2024 Jackal, by contrast, is just another content piece spat out by a TV giant’s algorithm. Everyone followed orders, mindlessly churning it out. This corporate drudgery seeps into the protagonist’s character and energy.

The series’ failure is no great loss. Pity for Eddie Redmayne’s intense, melancholy face, though. It could have conveyed a far richer soul. Instead, he’s reduced to a glamorous clothes hanger, hastily rushing towards the fate that awaits most modern content.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.