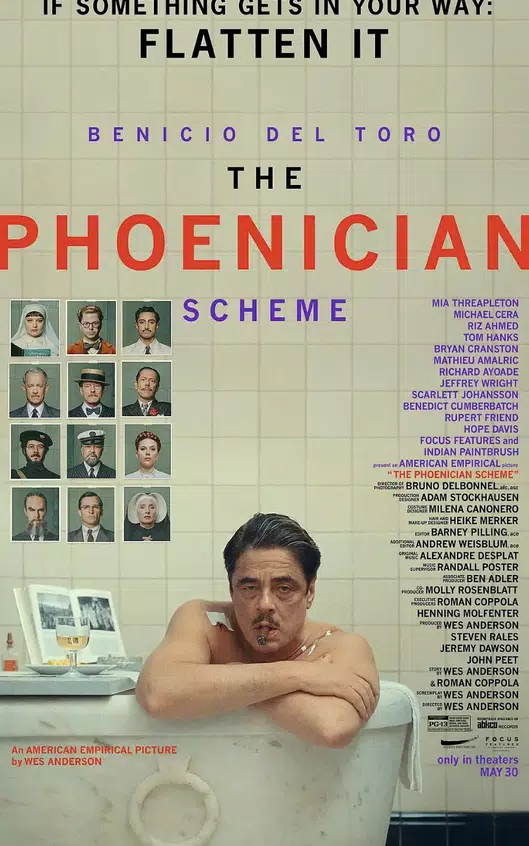

The Phoenician Scheme by Wes Anderson premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival. It showcased his signature style in a dazzling manner, and at the same time presented a raw exposure of the style’s inner conflicts. This dark comedy, centered on industrial tycoon Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro) and his fractured bond with his daughter, pushes Anderson’s trademark symmetrical visuals, nested storytelling, and whimsical colors to new heights. Yet, it also reveals a deep tension between form and feeling.

The film kicks off with a shocking mid-air assassination: Korda’s private jet is blasted over the Balkan highlands, the grim sight of torn bodies shattering Anderson’s usual candy-colored veil. Korda is a man who bends the world to his will. His ruthless ambition lets him manipulate people, labor, and resources with ease to build a fully integrated global industrial empire, no matter how many bureaucrats, politicians—or even assassins—try to stop him. He’s a master of survival and deal-making. It’s hard not to see echoes of a certain real-world American mogul: assassination attempts only seem to make him stronger; his business plans rely on convincing investors he has more cash than he does, and he dismisses ecology or human rights without a second thought. Korda is the ultimate capitalist titan, trampling bureaucracy and ethics, even turning murder attempts into PR stunts. Anderson, through the voice of Korda’s secretary Bjorn, nails his essence: he’s an invasive species, useless to the world but convinced of his own omnipotence.

Korda’s Phoenician Scheme” is a loaded metaphor. The Phoenicians were ancient trade pioneers and colonial expanders. In the film, the scheme is sold as a global industrial utopia but exposes the hollowness of unchecked capitalism. When Korda unveils a miniature model of a nation, like a perfect toy, Anderson stages it like a play, revealing how capitalism reduces human communities to manipulable parts. This critique of power builds on the nostalgic longing for old Europe in The Grand Budapest Hotel, but cuts like a sharp blade into today’s issues.

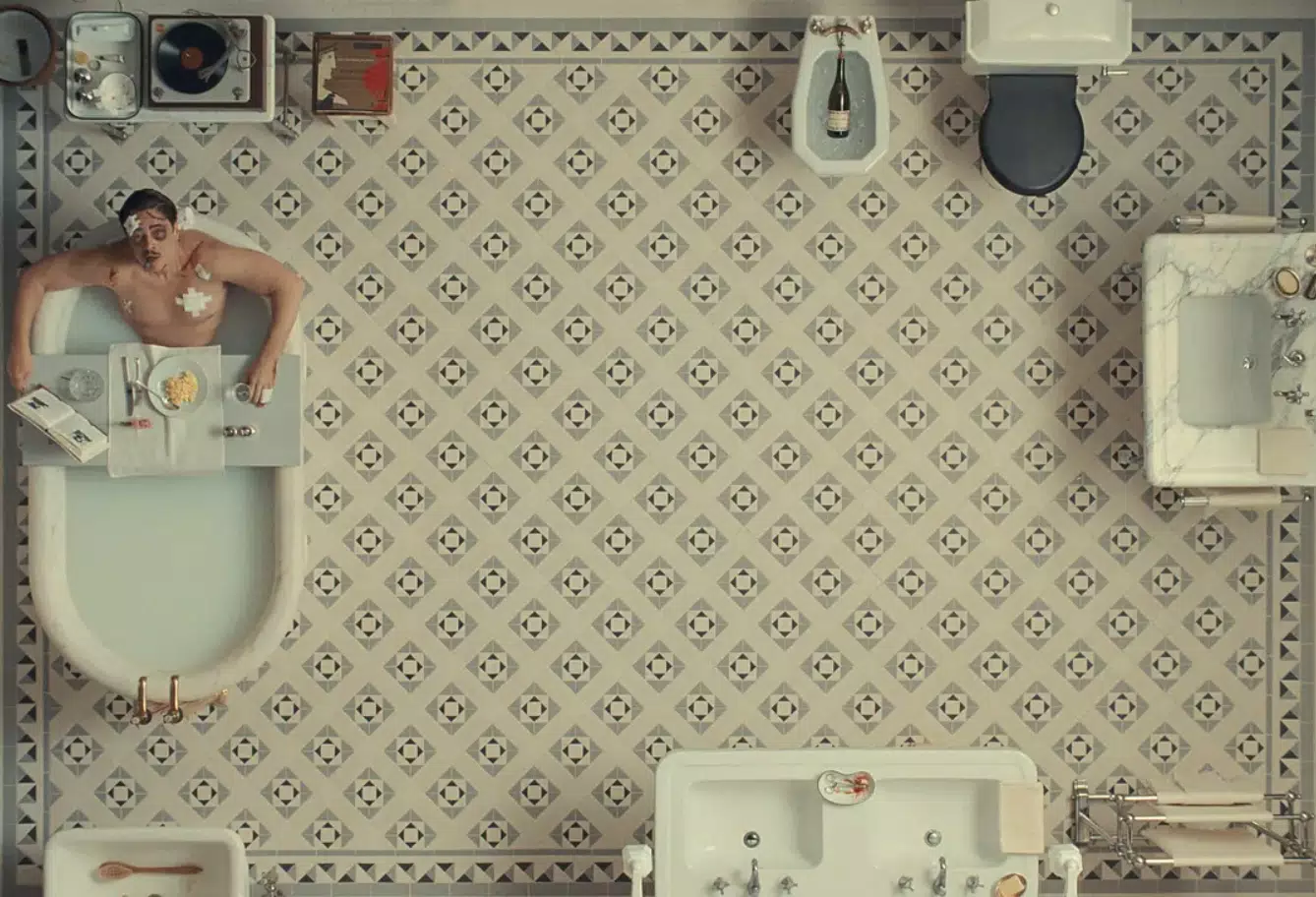

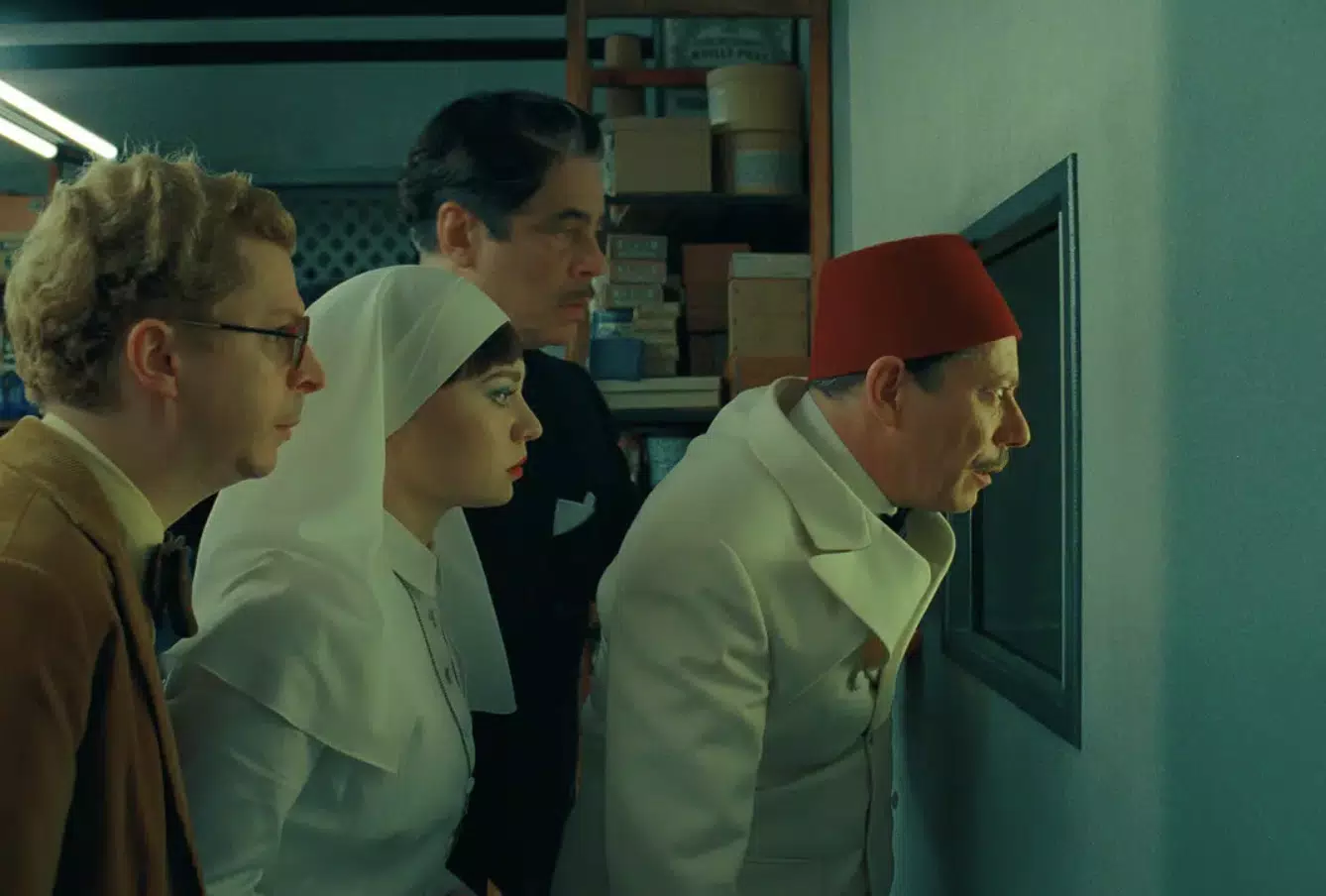

Visually, The Phoenician Scheme is Anderson at his peak. The movie is overloaded with symmetry. From precisely carved desert highways to perfectly aligned negotiation scenes, geometric order dominates like a visual tyrant. A standout moment is Korda’s basketball court pitch to a Middle Eastern prince: in a pastel blue setting, players move like clockwork gears, turning a business deal into an absurd physical ritual.

We can also find color as meaning. Anderson uses color to divide narrative spaces. Korda’s empire is cloaked in cold, metallic grays, while his daughter Liesl’s monastery glows in soft yellows, clashing power against faith. But when Nubar (Alexander Skarsgård) enters in stark black against pastel backdrops, he’s a visual void, echoing the villain Dmitri from The Grand Budapest Hotel. This color-stripping trick feels recycled, hinting at Anderson’s repetitive tendencies.

And narrative fatigue. The film’s five-act structure, each tied to a different investor, could have deepened the themes but fragments under rigid formalism. A tense French nightclub scene with terrorists should grip you, but symmetrical shots and slow motion turn it into a comical puppet show. As the camera pans across characters like a display case, viewers would find it hard to feel emotionally invested. Rather, they would feel like detached observers.

The film’s real heart lies in Korda’s relationship with his daughter, Liesl (Mia Threapleton). Forced to be his heir, Liesl believes Korda caused her mother’s death. Anderson weaves in the classic theme of absent mothers and fatherly redemption. Del Toro delivers his most layered performance yet: when Korda clumsily mimics a nun’s prayer to win over Liesl in a Beirut hotel suite, the titan shows rare vulnerability. Only when he stops chasing grandeur and embraces weakness does genuine tenderness break through the satire. Del Toro shines as a broken patriarch, while Threapleton subtly captures a disappointed daughter’s grace.

But Anderson seems trapped. Is his iconic style a signature or a cage? The Phoenician Scheme sparks debate because it lays bare Anderson’s creative paradox. It’s been called a “PowerPoint movie” since The French Dispatch. When Korda adjusts his tie clip under a terrorist’s gun, he’s less a character and more a puppet of Anderson’s obsessiveness. This “aesthetic tyranny” showed cracks in Asteroid City (IMDb 6.4, his lowest score), proving audiences are tiring of hollow perfectionism at the cost of emotional depth.

Nubar, the villain, feels like a rehash of The Grand Budapest Hotel’s Dmitri—same black attire, same brutal henchmen. The miniature nation model mirrors art-dealing scenes in The French Dispatch. These repeated motifs expose Anderson’s creative limits.

The film juggles gangster thrills, family drama and political satire, but rapid-fire dialogue and fragmented storytelling scatter the focus. Unlike the poetic child runaway tale in Moonrise Kingdom or the historical weight of The Grand Budapest Hotel’s escape, the genre mix here feels like a mechanical pile-up.

Still, dismissing Anderson’s effort would be unfair. The film’s breakthrough is its self-deconstruction. When Liesl knocks over Korda’s neatly arranged test tubes, letting colored liquids spill into chaotic stains, Anderson seems to confess: perfect form must yield to raw emotion.

In a way, The Phoenician Scheme is Anderson’s metaphor for his own struggles. Korda’s empire mirrors Anderson’s filmic kingdom—controlling actors (his regular crew like Bill Murray and Tilda Swinton are like Korda’s nine sons), marshaling resources (top-tier production akin to global capital), and facing “assassination” (critics like Nubar’s schemes). Liesl’s “monastery spirit” reflects audiences craving authentic connection. When Threapleton stares into the camera, asking, “What are you trying to prove?” it feels aimed at Anderson himself.

Cannes buzzed with debate: when form becomes the story, is the film a bold revolution or a polished prison? The Phoenician Scheme is more than a dark comedy or a visual feast; it’s Wes Anderson wrestling with his own legacy. Through Korda’s empire and Liesl’s rebellion, the film probes the cost of control—whether it’s capitalism’s grip on the world or a director’s obsession with perfection. By letting chaos seep into his meticulously crafted frames, Anderson hints at a deeper truth: true connection, whether between father and daughter or artist and audience, demands vulnerability over polish. The film’s heart lies in this tension, making it a bold, if flawed, meditation on power, art, and the courage to let go.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.