As a film, Gladiator II was never really expected to succeed. The original Gladiator, released 24 years ago, told a complete and triumphant story. It left no loose ends and no gaps requiring closure. And in today’s era, where masculinity and individual heroism are being reevaluated, replicating the success of Gladiator seems nearly impossible. Even more so when this era can no longer produce a masculine icon like Russell Crowe—a primal force of manhood—or if it could, such a figure would likely fall from grace as quickly as they rose.

As a film, Gladiator II was never really expected to succeed. The original Gladiator, released 24 years ago, told a complete and triumphant story. It left no loose ends and no gaps requiring closure. And in today’s era, where masculinity and individual heroism are being reevaluated, replicating the success of Gladiator seems nearly impossible. Even more so when this era can no longer produce a masculine icon like Russell Crowe—a primal force of manhood—or if it could, such a figure would likely fall from grace as quickly as they rose.

So, what is the purpose of making a sequel to Gladiator?

Perhaps only Ridley Scott himself needed this sequel. In the original film, he couldn’t create the naval battle spectacle he envisioned due to budget constraints. This time, with a more generous budget, he finally fulfilled his ambition. Whether this is the spectacle audiences wanted is another question entirely.

Objectively, however, Gladiator II does carry a certain narrative necessity. From the first film to the second, 24 years have passed. Has the world truly improved during this time?

For many, the answer is likely a resounding no. Or, to put it another way, while the world may not have grown worse in the past 24 years, people's hopes for the future have certainly dimmed. Political gridlock, widening wealth gaps, ideological polarization, and the ever-looming possibility of war have eroded dreams of a better world. In today’s world, mere survival amidst chaos feels like the most rational choice.

The premise of Gladiator II reflects our contemporary reality. Critics have faulted the film for undermining Maximus’ efforts in the original by rendering them futile at the sequel’s outset. Yet this narrative choice mirrors not just ancient Rome but our modern world. In it, characters like Acacius—noble in spirit and clinging to remnants of idealism—find themselves exhausted and marginalized, while opportunists like Macrinus, who thrive in a survival-of-the-fittest order, rise like mushrooms in a dark, decaying environment. Meanwhile, those nominally in charge of the world’s order are inept fools, whimsically waging wars and punishing the populace, blissfully ignorant of their impending doom.

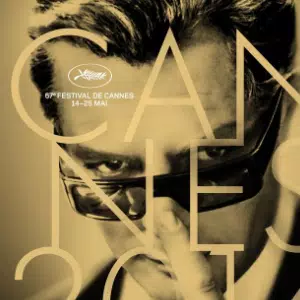

This cynical view of history is not new in Ridley Scott’s work. While many still associate him with the grandiosity of Gladiator, the dystopian poetry of Blade Runner, or the patriotic fervor of Black Hawk Down, his recent films have systematically deconstructed grand narratives. Prometheus and Alien: Covenant dismantle anthropocentrism; The Last Duel deconstructs male honor as vanity and weakness; House of Gucci and All the Money in the World expose the hollow glitz of success; and Napoleon completely shreds the myth of the "great man" view of history. Late-career Ridley Scott seems like an old man disillusioned with the world, and this sense of disgruntled futility permeates his films.

In Gladiator II, Paul Mescal’s Lucius, son of Maximus, continues to rally for a renewed Roman dream. Yet his calls for action feel feeble in the face of the jungle-like order that dominates the world, making Macrinus’ assertion more persuasive:

Marcus Aurelius’ republican dream wasn’t a dream—it was a fiction. A freed slave doesn’t settle for liberty; he wants slaves of his own. That’s the reality of this world.

Under the weight of such impotence, the heroic narrative that should drive the film naturally feels weak and anemic. Gladiatorial combat sequences, which should ignite adrenaline and provide a thrilling experience for viewers, come across as perfunctory and half-hearted. When the creators themselves lack faith in their idealism, how can a film meet expectations of being a grand epic?

The decline of ancient Rome and the decline of our contemporary world seem inescapable. Similarly, the decline of the live-action blockbusters is something that an 87-year-old Scott cannot reverse. Traditional cinema, rooted in the theater-going experience, is becoming antiquated in an age fragmented by smartphones and social media. With such an irreversible loss of attention span, what can even a master like Scott do? Cinema as a medium and a place, once rivaling churches, masses, and novels, now crumbles like the Roman Empire. And the once-godlike actor has become a bloated rancher, leaving audiences only with sighs of nostalgia.

Ultimately, the assessment of Gladiator II depends entirely on the viewer’s perspective. If one expects a stirring, irony-free classical epic, disappointment is inevitable. Yet, that isn’t necessarily the creators’ fault. Calling for Homer or Virgil in an era devoid of heroism is as futile as clinging to a sinking ship.

But if one seeks to glimpse a reflection of our times, Gladiator II serves as an ideal case study. It highlights the impossibility of old values in the modern age. Those values, though weakly lingering, are but masks worn by people who have long abandoned any hope in them.

Perhaps it is indeed time for a true revolution.

Join the conversation and share your thoughts!

Join the conversation and share your thoughts!