Gene Hackman is an actor who is often subjected to a certain stereotype. He has long been known within the industry for his tough, no-nonsense demeanor, sometimes even being considered difficult to work with. His two Academy Award-winning roles—Popeye in The French Connection and Little Bill in Unforgiven—only reinforce this image, portraying him as a rugged, even ruthless character.

Yet, a closer examination of his career reveals a much broader spectrum of performances. Take, for instance, his role in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), where he plays a still-tough yet childlike and endearingly affectionate patriarch. Or consider Scarecrow (1973), where his character Max starts off as a hardened, cynical drifter, but gradually sheds his tough exterior under the influence of his optimistic friend Lionel. In an ironic turn, by the latter half of the film, Lionel—once full of youthful innocence—becomes disillusioned by life’s hardships, while Max’s latent warmth and loyalty come to the forefront as he steadfastly supports his fallen friend.

Then there’s The Conversation, arguably Francis Ford Coppola’s most underrated masterpiece, which showcases yet another uncharacteristic side of Hackman. In it, he plays a lonely, fragile, and almost pitiful surveillance technician—a man who excels at his work but is utterly incapable of integrating into society. His paranoia keeps him at arm’s length from others, and on the rare occasions when he does let his guard down, he is met with severe betrayal. Misfortune and despair cling to him relentlessly, until he is stripped of his identity, privacy, and dignity—only then finding a semblance of release.

Hackman’s character, Harry Caul, is a surveillance expert who operates independently, making a living by eavesdropping on and recording the conversations of others for his clients. His role strongly resembles the private detectives of 1940s Hollywood noir, but unlike those charismatic figures, Harry is devoid of charm, avoids contact with those he spies on, and shuns the spotlight. Fresh off The Godfather, Coppola further honed his low-light cinematography in The Conversation, visually reinforcing Harry’s psychological state—he is most at ease in the shadows, but whenever he steps into a bright, open space, his anxiety and paranoia flare up. Hackman’s subtle body language—outwardly composed yet internally on edge—effectively portrays Harry’s neurosis, embodying a modern anti-hero tormented by the weight of knowing too much in an age of pervasive surveillance.

But secrecy is only half of Harry’s burden. The other half is the deep guilt he carries for his profession. Unlike the protagonists of classic hardboiled detective novels, who stride through the world with moral conviction, Harry is acutely aware of the inherent unethical nature of his work. This constant tension traps him in a cycle of anxiety and self-reproach, never allowing him true peace of mind.

Harry’s guilt and paranoia lurk beneath his cold exterior, making him an easy target for those who can exploit his vulnerabilities. The Conversation unfolds as an elaborate trap set for him, and lacking confidence, self-assurance, and any sense of love or belonging, Harry is doomed to walk straight into it. His downfall is inevitable. Hackman fully abandons the rough, commanding persona he displayed in The French Connection just three years earlier, instead immersing himself in Harry’s insecurity, fragility, cowardice, and inner turmoil. At times, his fetal-like body posture starkly exposes his helplessness and lack of self-confidence, while the translucent raincoat he wears in many scenes serves as a metaphorical membrane, making him appear like an embryo still confined within the womb. He never seems to have fully matured into a functioning adult in this harsh world, and therein lies the profound tragedy of his character.

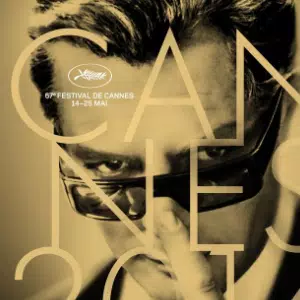

As an art film, The Conversation holds immense historical and thematic significance. It won the Palme d’Or at the 1974 Cannes Film Festival, stands as a cornerstone of the New Hollywood movement, and represents the peak of 1970s American thriller cinema’s paranoid aesthetic. The timing of its production and release coincided precisely with the unfolding of the Watergate scandal, cementing its status as a film that captured the zeitgeist of a deeply distrustful era.

Yet, its relevance has only grown with time—far from being outdated, it feels even more prescient today. The methods of surveillance employed by those in power and big corporations have become far more sophisticated and pervasive. In this age, we are all versions of Harry Caul from The Conversation’s final scene—laid bare before the world, stripped of privacy. The only difference is that, unlike Harry, most of us have ceased resisting and have accepted our reality without a fight.

The 1970s also marked a unique era of cinematic aesthetics, one that embraced unconventional leading men. Actors like Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, Harvey Keitel, and Jack Nicholson—none of whom fit the traditional mold of a Hollywood heartthrob—were able to become major stars based purely on their raw talent and their ability to bring authenticity to everyday characters. They could carry the weight of an entire film on their shoulders, something that had never happened before and has rarely been seen since. Hackman remained active in big-budget Hollywood productions throughout the 1990s, but by then, the industry had changed—leading roles were no longer built around performers like him, even though he still had the capability to carry a film single-handedly.

Reflecting on Hackman and The Conversation is like looking back at a lost golden age of cinema—an era when filmmakers confronted reality rather than dressing it up with slogans, and when actors with unconventional appeal fearlessly bared their weaknesses, insecurities, and even ugliness on the big screen, trusting that truth and vulnerability carried their own inherent power. Gene Hackman retired from acting years ago, and with his passing, another piece of that era faded away. It is only right that we honor his career and the masterpieces he left behind, for actors of his caliber are never a given—they are a rare gift.

View replies 2

View replies 0

View replies 0